Conspiracy theories and hoaxes abound when it comes to mankind’s arrival at our moon (or the non-arrival.) One such hoaxes is the Apollo 20, a purported top secret mission that back to the moon back in 1976 to fetch some aliens living there. The secret would have been revealed by no other than William Rutledge, who claims to have been an astronaut in that mission and who nowadays lives and writes out of Rwanda.

Arguably this theory was never as popular as its always popular theory that NASA spent billions of dollars to fabricate the moon landings but somehow forgot to paint stars in the ceiling.

Now however a film promises to inspire the masses who believe NASA has been sending secret missions to Luna. The movie is Apollo 18.

(Promotional picture)

The movie’s premise is that after the Apollo program was cancelled, NASA would have flown another mission and found, of course, aliens and that’s why we’ve never been back to the Moon. It’s one more movie in the style of Cloverfield, where the audience is expected to pretend to be watching to real top-secret leaked footage.

Domension Films’ big cahuna, Bob Weinstein, stated,

We didn’t shoot anything, we found it. Found, baby!

The movie is of course a work of fiction. That’s not hard to figure out, even if you could not look up the actors who were in the movie. For instance, the astronauts of Apollo 18 in the movie are supposed to be Nathan Walker, John Grey e Benjamin Anderson, but the astronaut corps roster was very well known and none of these gentlemen were part of it. Although none of the crews for the cancelled flights (Apollos 18, 19 and 20) were never officially named – what would be the point? –, one can infer from the assignment rotation system NASA used that the Apollo 18 crew would likely be:

- Richard Gordon

Vance Brand

Harrison Schmitt

Except Schmitt was activated to the Apollo 17 main crew when it became clear that it would be the last chance for a scientist to step on the moon. Somebody – Joe Engle, perhaps – would have to replace him on Apollo 18.

But the hoax is not really about the movie itself, but about the general idea that NASA ran more missions than we know about. So, could something like Apollo 18 really have existed? Could NASA have performed this secretly?

It is unfortunately impossible to prove a negative, but at least we can think of how likely would that be. I can’t really see how such a thing could have been done. To begin with, there’s this:

(Image credit: Euclid vanderKroew)

You see, the Saturn V was big. Really big. Not easy to hide, then. It seems highly unlikely that NASA could have launched a Saturn V out of Cape Canaveral without it being seen.

I also saw this argument on some forum that NASA would have prefferred a night launch to improve the chances to keep it a secret, but the thing is, that big dumb rocket is not very subtle either.

(Image credit: Euclid vanderKroew)

And then if we discard a launch in the continental US, it would have to be from either a platform at sea or from somewhere in North Africa. Problem here is that the logistics of accomplishing such an feat – let alone in absolute secrecy – are just fenomenal.

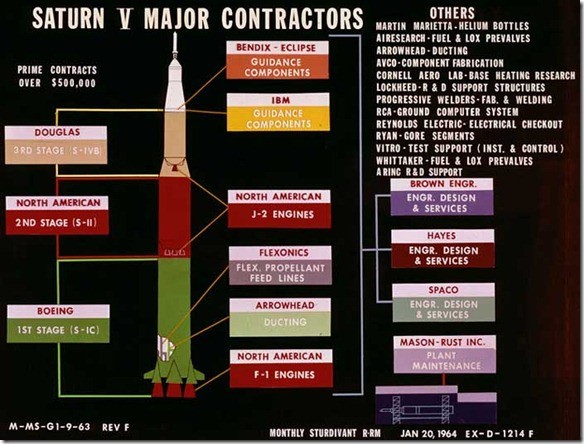

As well, the Saturn V was a very public project. All its parts were very well tracked and it’s possible to know where most parts are even today. And some of those parts are huge, not the kind that you can stow in the back of a black unmarked van.

And then there are other factors, of course. We’re used to the image of three astronauts sitting on top of a rocket and a mission control room with, say, 20 or 30 people.

(Image credit: Cory Doctorow.)

But an Apollo flight involved a lot more people than that. In A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts

But an Apollo flight involved a lot more people than that. In A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts (Awesome gift! Thank you Stulzer!), Andrew Chalkin estimates the figure at 500,000 workers altogether. Others state the number is more like 400,000 people.

(Awesome gift! Thank you Stulzer!), Andrew Chalkin estimates the figure at 500,000 workers altogether. Others state the number is more like 400,000 people.

Regardless of the actual figure, it should be clear that such a mission would require the collaboration of hundreds of thousands of people all around the world (more on that below.)

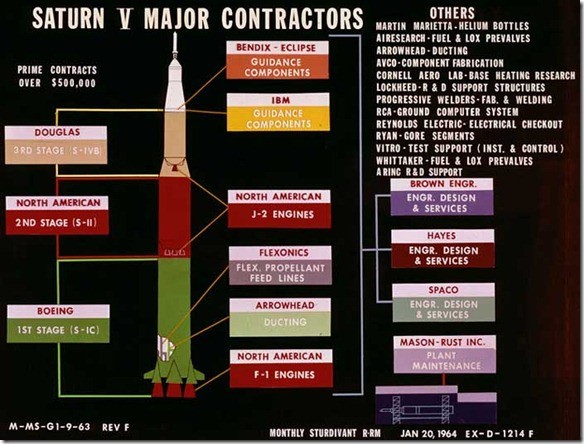

And contrary to what some might want to believe, the Apollo program was not something entirely done behind closely guarded doors at some Air Force base. It involved a lot of private contractors. GE, IBM, Boeing, GM… the list of contractors can occupy several pages. To assume that all the employees involved who have since likely changed jobs multiple times and retired would be able to keep this a secret for four decades really stretches one’s imagination.

(Image credit: history.nasa.gov)

As big as the contractors’, the list of academic institutions involved in the program is amazing. Virtually every major US university and institute was included, but the list also included institutions form Australia, Belgium, Canada, England, Finland, Germany, Japan, Scotland and Switzerland. And that takes me to what is, to me, the most important thing to consider.

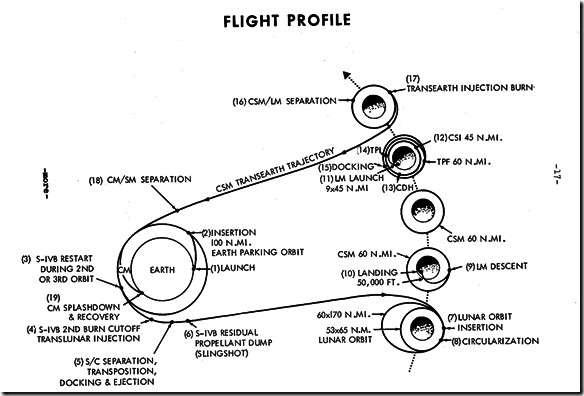

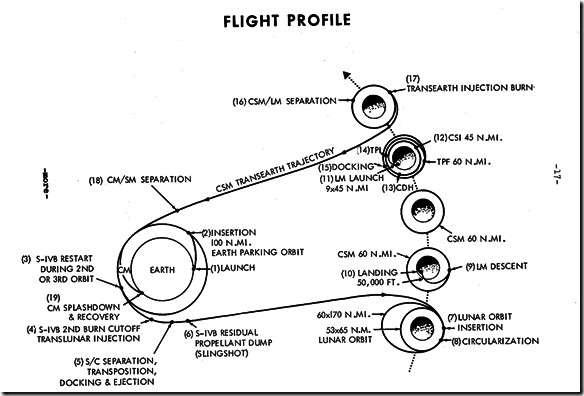

In order to fly to the Moon, you don’t just point the rocket, turn on the ignition and wait for it to reach its destination. It’s a complex voyage with huge preparations, calculations and adjustments. Orbital mechanics was one of the most interesting things I’ve even studied. But I digress.

An interesting challenge for NASA was to be able to communicate and track the ship all the way to the Moon and back.

(Escaneado pelo autor. NASA Apollo 11 Press Kit Pg 17)

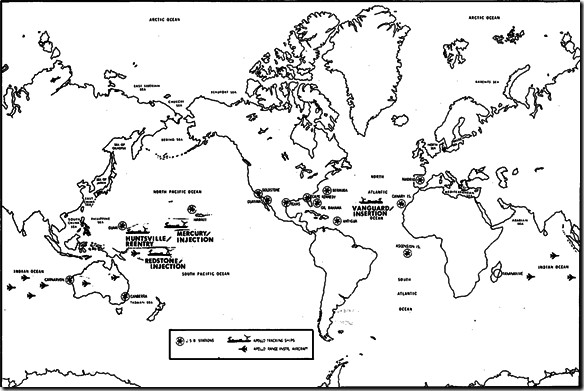

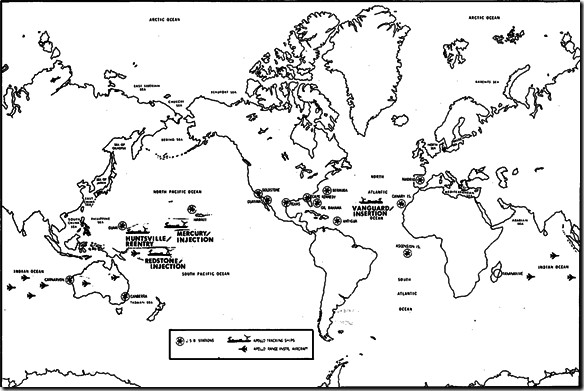

Nowadays NASA added a whole network of satellites to assist the tast, but back when Mercury and Apollo were underway, the tracking depended on a network of tracking stations, vessels and aircraft all around the world.

That network was the Manned Space Flight (Tracking) Network. Starting from Apollo 10, the Deep Space Network was added to assist.

(Scanned by the author from NASA Apollo 11 Press Kit, Pg 172)

It’s interesting to know that over the course of its evolution, NASA’s networks included a station in Havana, Cuba. That station was dismantled after years of service due to the Cuban revolution. As Brazilian, I also find special interest in that there was even one station along with the Brasilia International Airport, even though it was quickly disassembled and shipped to Madagascar.)

Although those were NASA installations, they employed locals. These stations all around the world had been performing duties for years under heavy media scrutiny and to expect that all of a sudden they would be able to do it in complete secrecy is beyond reasonable belief. That and the local workers who also had to keep secrets for four decades make the most absurd hole in the hoax.

Now remember that the Apollo missions were tracked and monitored by several governments including, of course, the Soviet Union. In Two Sides of the Moon , Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov – trained to be the first man on the moon – states that all the missions were followed by the Russians in a very well equipped Space Transmissions Corps, in Moscow. Now you need the secret to be kept by the Soviets and then, after the USSR fell, by the several nations that sprouted from it.

, Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov – trained to be the first man on the moon – states that all the missions were followed by the Russians in a very well equipped Space Transmissions Corps, in Moscow. Now you need the secret to be kept by the Soviets and then, after the USSR fell, by the several nations that sprouted from it.

And the Apollo missions were tracked by amateur astronomers and radio operators all over.

Of course that nothing here proves beyond any doubt that such secret missions were impossible, just unreasonable unlikely. But since you can’t prove a negative, no matter how improbale, there will still be plenty of people who believe.

(Awesome gift! Thank you Stulzer!), Andrew Chalkin estimates the figure at 500,000 workers altogether.

(Awesome gift! Thank you Stulzer!), Andrew Chalkin estimates the figure at 500,000 workers altogether.

, Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov – trained to be the first man on the moon – states that all the missions were followed by the Russians in a very well equipped Space Transmissions Corps, in Moscow. Now you need the secret to be kept by the Soviets and then, after the USSR fell, by the several nations that sprouted from it.

, Russian cosmonaut Alexei Leonov – trained to be the first man on the moon – states that all the missions were followed by the Russians in a very well equipped Space Transmissions Corps, in Moscow. Now you need the secret to be kept by the Soviets and then, after the USSR fell, by the several nations that sprouted from it.